1950s-1960s

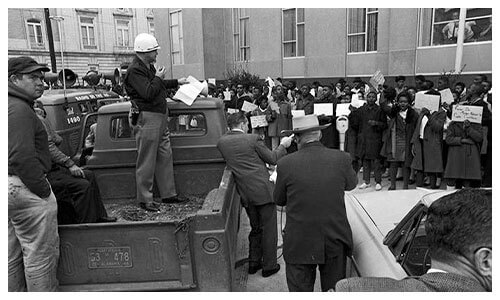

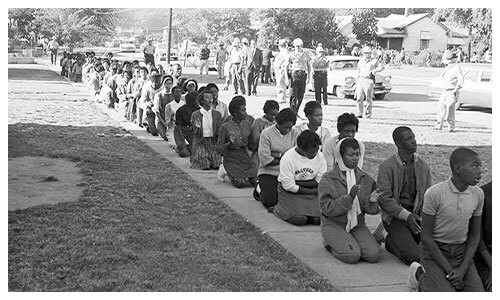

Voter registration efforts

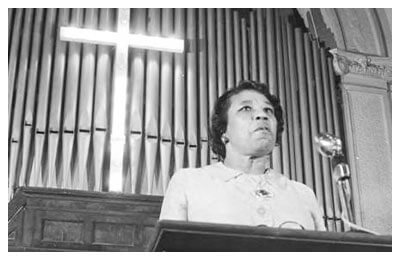

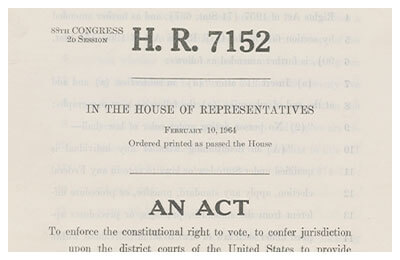

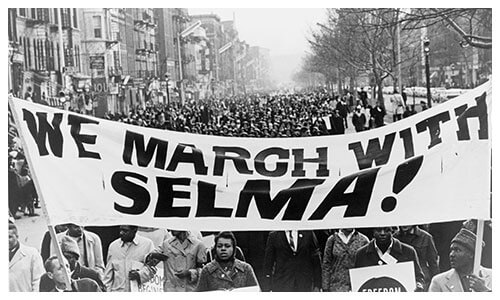

Long before 1965, when the Voting Rights Act was signed into law, local Black activists along with the organization Dallas County Voters League (DCVL) in Selma had been campaigning for Black people’s right to vote. Violence, economic intimidation, and racist policies kept the numbers of Black registered voters small. But in the late 1950s to early ‘60s, the DCVL steering committee, who later became known as the “Courageous Eight,” bravely stepped up to lead registration efforts. The Courageous Eight included Ulysses Blackmon, Sr., Amelia Boynton, Ernest Doyle, Marie Foster, James Gildersleeve, Rev. J.D. Hunter, Sr., Rev. Henry Shannon, Sr., and Rev. Frederick Douglas Reese.