selma

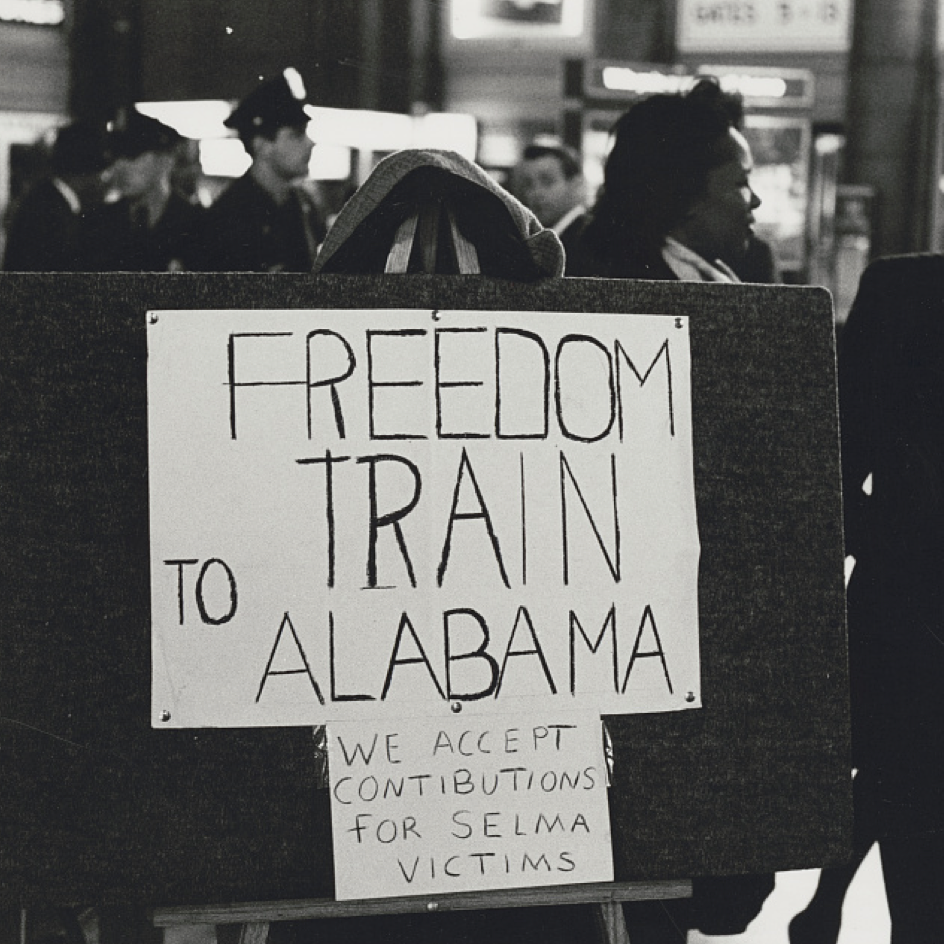

On March 7, 1965, around 600 protesters led by John Lewis and Hosea Williams were attacked by Alabama state troopers as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Their plan was to march from Selma to Montgomery to demand the right to register black voters in Alabama. The indelible images from that day, which became known as Bloody Sunday, documented both heroic bravery and unspeakable brutality. They shocked the world and focused national attention on the rampant injustice and racism faced by millions of black Americans.

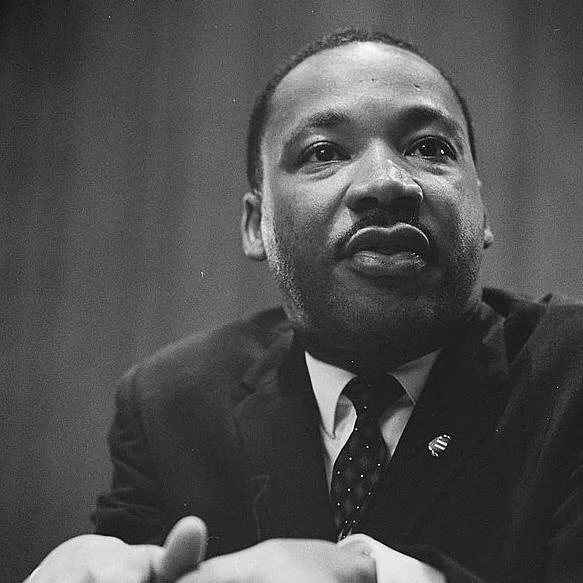

On March 21, Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. and John Lewis attempted the march again. 600 had become 8,000 as they marched out of Selma. By the time they entered the state capital, their number had grown to 25,000 as young people from across the county flocked to Alabama to support the cause. These acts of courage turned public opinion in favor of the Voting Rights Act and pressured congressional lawmakers to pass the landmark bill.

Yet, despite its hallowed place in American history, Selma today is one of the poorest cities in Alabama: 41% of its residents live in poverty and the average household income is almost half the state average.

The development of Foot Soldiers Park and Education Center will bring much-needed jobs and revenue to the city. In addition to economic opportunities, the development will instill civic pride and a connection to their noble history for the young people who reside there today.

Below is a brief timeline of the pivotal events of 1965.

The city of Selma played a pivotal role in the Civil Rights Movement

of the 1960s. It is the site of some of the most famous and consequential acts of peaceful protest in American history.

A Very Brief History of the Selma Movement

February 26, 1965

Jimmie Lee Jackson, a veteran, Baptist church deacon and voting rights activist, dies after being beaten and shot by an Alabama state trooper while participating, unarmed, in a peaceful voting rights march in Marion, Alabama. His death sets off a new phase in the struggle for voting rights in Alabama and beyond.

March 7

Led by John Lewis and Hosea Williams, a group of over 600 marchers, most of them young people including children and teens, gather on a cement basketball court located within the George Washington Carver homes in Selma. Their gathering site is steps from the Brown Chapel, home to countless community organizing meetings and rallies, including those led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Their plan is to march to Montgomery to advocate for voting rights.

As they march towards the Edmund Pettus Bridge to begin their journey, the protesters are met by county sheriff Jim Clark’s deputies, many on horseback, and armed Alabama state troopers, who have been ordered by Governor Wallace to “use whatever measures are necessary to prevent a march.” The peaceful protesters are brutally beaten; photos and video of the violence are broadcast around the world.

March 9

Led by Dr. King and faith leaders from around the country, marchers again try to make their way from Selma to Montgomery and are once more met by police. Rather than engaging in a confrontation, Dr. King encourages the marchers to disperse. This is now known as Turnaround Tuesday.

That night, James Reeb, a Unitarian Universalist minister who traveled from Boston to participate in the marches, is savagely beaten by members of the KKK. Two days later, at the age of 38, he dies from his head injuries. One of his children, Anne Reeb, is involved with our efforts to preserve this history and the memory of her father.

March 20

President Lyndon Johnson issues an executive order authorizing the federal use of the Alabama National Guard to provide protection to the marchers. He also sends 1,000 military policemen and 2,000 Army troops to escort the marchers from Selma.

March 21

About 8,000 people assemble at Brown Chapel and at the Carver Homes area and begin the five-day march to Montgomery's Capitol.

March 25

By the time the protesters reach Montgomery for a final rally at the state Capitol, their number has increased to 25,000 as young people from across the country flock to join the march.

King delivers his famous "How Long, Not Long" speech.

That night, Viola Liuzzo, a white mother of five who had driven from Detroit to help protest for black civil rights, is shot and killed by the KKK while driving to Montgomery to pick up a carload of marchers. She was 39. One of her children, Mary Liuzzo Lilleboe, serves on Foot Soldiers Park’s Board of Directors.

present day

JoAnne Bland

My Dream for Selma & My Vision for Foot Soldiers Park

During my lifetime, I have been both a witness and a participant in some of our nation's most consequential civil rights battles. I was born and raised in Selma, Alabama, and have seen first-hand how racism and segregation created a deadly divide between people--neighbors, co-workers, classmates--and I decided early on that I would always try to lift my voice to decry injustice wherever I saw it.

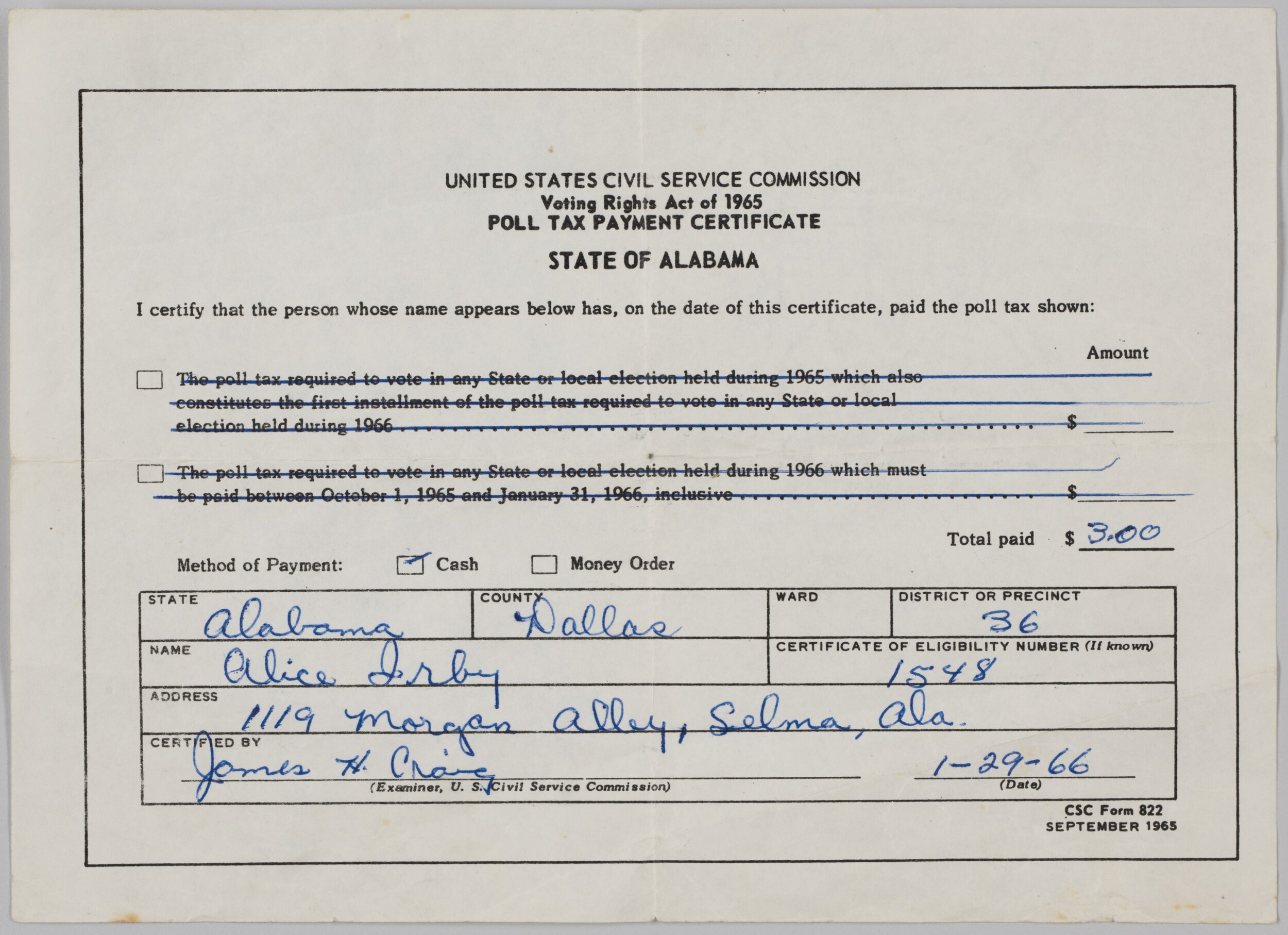

In the early 1960's, I joined my grandmother at Dallas County Voters League meetings led by the great Amelia Boynton. I began my own activism, with SNCC (The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee), at the age of 8 along with other children and teens in my neighborhood. We all wanted to do our part to make the goals of the Civil Rights Movement, equal justice and equal treatment, a reality for ourselves and our families.

By the time I was 11 years old, I had been arrested 13 times that are documented. I was an active participant in Bloody Sunday, marching alongside more than 600 peaceful activists only to get brutally beaten, tear-gassed and hit by policemen on horses with billy clubs

My early involvement in the struggle against "Jim Crow", our American apartheid, has been the foundation and fuel for my civil and human rights work.

I served in the US Army and returned to Selma to co-found and lead the National Voting Rights Museum, and now lead a tour company that welcomes visitors from around the world. As I lead groups through Selma now, on the trail of the foot soldiers of 1965, we see clearly the connections between our history and our current reality. Visitors gather with me on the same patch of cement that I stood on March 7th, 1965 with John Lewis, Hosea Williams, and Amelia Boynton. I give each visitor a small stone that has chipped off this cement as a symbol of their connection to these leaders and their role in carrying on the movement for social change.

I believe that movements for social change are like jigsaw puzzles. Everyone is a unique and special piece. If your piece is missing, the picture is not complete. Why? Because you're the most important piece.

My dream for Selma is that it will become a place of pilgrimage for all those who seek to right the wrongs of our society, both in our state, our country and around the world. My vision for preserving the hallowed ground where the Bloody Sunday march began and creating Foot Soldiers Park is to show every visitor, and especially every child, that they have the power to make great change in their community. The little boy who plays in our playground can see himself in Congressman Lewis’ courageous image, and the little girl who kicks a soccer ball on our fields can see herself in the tenacity of Ms. Boynton. It is my greatest hope that this city and this site are treasured and honored long after all of us, the original foot soldiers, have passed.

With gratitude,

Please visit our partners from Harvard's Hutchins Center

for African & African American Research at Selmaonline.org

to learn more about the Selma movement and how this history connects to the issues and activist movements of today.

Yesterday

Today